![[]](./bin/ailogo.gif)

Website Provider: Outflux.net

URL:http://jnocook.net/texts/books.htm

Photographic BOOKS -- Jno Cook

This was part of a handout about visual books for a class. I have

dropped the arcane references to book in the middle ages, and some other

forms, and just retained here the core of "photographic" books, and a few

I really like.

19th Century and earlier

These are photographic (or photo-based books) worth

seeing. I'm not listing books which are just retrospectives and

collections (except a few), they are seldom interesting and never have a

theme. I am listing some books other than photographic books if they are

of some importance to the visual arts community.

|

Fransisco Goya's "Los Caprichos" (1799), is a portfolio of single prints.

There is a 1969 Dover reprint. Always great to look at again. If you could

photograph like he draws, you would be the formost cultural critic of

today. |

The 19th Century sees the development of offset

printing methods, and high-speed machinery. By the end of the century the

half-tone process has been developed, and already multicolored images are

found in books, magazines and catalogues. Although color photography had

to wait until 1936, color separations were made since the 20's (the

3-color additive printing process dates from the middle of the 19th

century).

But mostly throughout the 19th century, and increasingly since

photography became available, illustrations -- in woodcut and engravings

-- were the property of magazines and catalogues.

Check out, for example, Honoré Daumier, 1808 - 1879,

who produced some 4000 engravings for weekly newspapers between 1830 and

1870. But it's not a book. That is, it is not presented as a definitive

collection, like Goya's work. And these illustrations depended heavily on

captions. After 1865, however, photography enters the book.

| Alexander Gardner "Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War"

(1866), in two volumes, 100 tipped-in photo prints (Dover reprint 1959).

There is a text apposed to each photo. |

There was a question, for Gardner as for Emerson

(below), as to whether photographs could be presented without text, or

with just a minimal text. Only Muybridge (below), in the 19th century,

got away without text, for his photographs were presented only as visual

evidence.

| P. H. Emerson: "Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads" (1886),

and five more like this up to 1893. Most are illustrated in gravure, a

process which comes as close -- in ink -- as possible to looking like an

actual photograph, and all carry texts. Emerson's books became the model

for illustrated ethnographic picturebooks for the next 50 years. Shown is

a 1975 biographical compilation of Emerson's work by Nancy Newhall.

|

|

| Eadward Muybridge "Animal Locomotion" (1887), in 11 volumes (!)

These are 781 "studies" each composed of 20 to 40 photographs each, that

is, per page, for a total of some 24,000 photographs! The exhaustiveness

is overwhelming. There's a "Human Locomotion", too. Reyerson has a number

of copies, some with carefully removed human body parts. Original

printings were in colotype. Shown here is a 1955 reprint of "Human

Locomotion." |

Early 20th Century

Throughout the 19th and most of the 20th century the

use of photographic books remains directed toward ethnographic (when it is

'them') and photojournalistic (when it is 'us') uses, and, of course, the

sort of travel pictures from strange places and foreign lands (they start

as early as 1852 with "Egypte, Nubie, Palastine et Syrie", as engravings

from Daguerreotypes). And then there are all those how-to manuals. A few

stand out as interesting, but all of them depend on text.

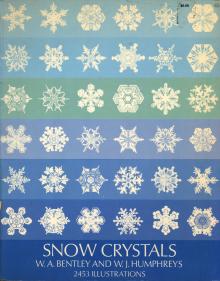

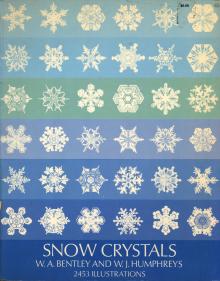

| W.A. Bentley "Snow Crystals" (1931) (Dover reprint 1962) An

unbelievable collection of 2500 snow flake images, page after page after

page, all taken with an 8x10 camera in freezing weather. But no supporting

text. |

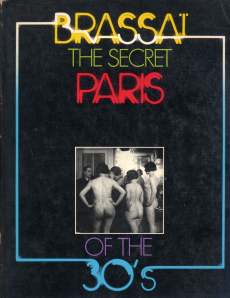

| Brassaï "Paris de Nuit" (1933), reprinted as (although not

the same book) "The Secret Paris of the 30's" (1976). |  |

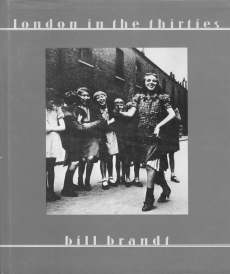

| Bill Brandt "The English at Home" (1936) "London in the thirties"

(1983) is a recent compilation. |

Dorothea Lang and Paul Taylor "An

American Exodus" (1939) The classic Lang book on the depression, and the

farmer migration to California.

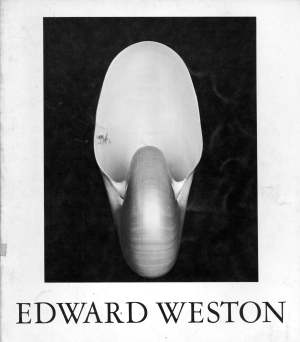

Edward Weston "California and the West" (1940, 1979) and "The

Daybooks of Edward Weston" (1961, 66, 2 vol). The daybooks are interesting

reading, but selfconsciously edited. |  |

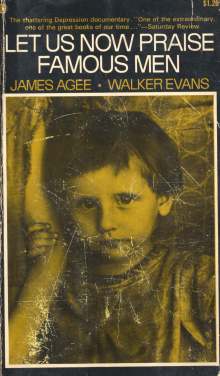

| Walker Evans and James Agee "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men"

(1939, reprinted in 1960 and 1966, 1975, 1989). Only some 60 photographs,

which precede the text and even the title page of the book. And a

heart-wringing text of hundreds of pages by Agee, which must have cost him

his soul to write.

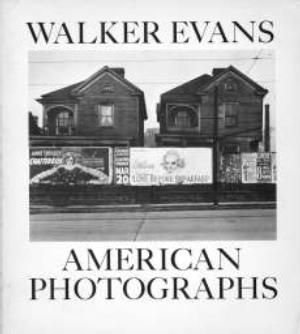

But Evans' reputation rests mostly on "American Photographs" (1938),

which is actually an exhibition catalogue put out by MoMA, and reprinted

in 1962. Embarrassingly for the Museum, the catalogue was entirely put

together by Evans and critic Greenberg -- for the curator was away at the

time of the exhibition. "American Photographs" sold only a few copies, but

it was one of the most influential books of the 40's and 50's. Walker's

best work may be "Messages from the Interior" 1966, which is only 12

photographs. |

| Weegee (Arthur Felling) "Naked City" (1945). A newspaper

photographer living out of his car in the 40s. Shown here is a 1973

reprint. |  |

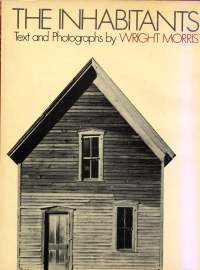

| Wright Morris "The Inhabitants" (1946) "The Home Place" (1948)

"God's Country and My People" (1968). Some of it is in the tradition of

Walker Evans, but somehow the aesthetic is not the same. |

After the middle of the 20th Century

Henri Cartier-Bresson

"The Decisive Moment" (1952) This presented a photographic approach which

suggested that intelligent camerawork could usurp for the professional the

candids which so often fell into the lap of the amateur. It became a

cul-du-sac, however, in that the professionals were deadlocked in a race

for precision, with Cartier-Bresson in the lead.

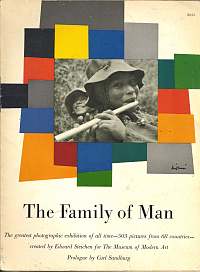

| What Evans had pointed to in 1938, that is, leaving the text

behind, Edward Steichen undertook as a project in 1956, when he opened the

show "The Family of Man" at MoMA. The catalogue (same name) for this

exhibition should be looked at, for it brought photojournalism, as it had

been understood for over a hundred years, to an end. The premise was that

photography was a language. It took Robert Frank (below) to point out that

this was not so. It should also be looked at because you might wonder how

one book of photographs could sell over 4,000,000 copies, and still be in

print today, when most books of photographs sell 500 to 1,000 copies.

|

| William Klein "New York" (1956), actual title is "Life is Good

and Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels". Picture captions

are inserted as a small booklet, in French. Klein is a designer,

filmmaker, and photographer. His photographs of New York 'in the raw'

rival Robert Frank's. Klein was way too far ahead of his time. Shown here

is one page from "New York." |  |

|

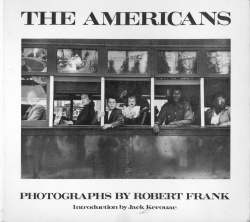

Robert Frank, "The Americans" (1959, 1968, 1978, 1988, 1998). A book

of 83 photographs which stand completely on their own (you are reminded of

Goya's 80 plates, "Los Caprichos"). A bitter social critique, a sad and

personal poetry of hopelessness, and a pointed review of photography -- it

can be seen, even, as a textbook on photojournalism. The integrity of

"The Americans" is absolutely amazing. And it stood photography on its

head. When it was reprinted in 1968 other photographers started to take

notice not just of the pictures, but of the book. The result has been a

flood of photo books, often entirely based on a misreading of "The

Americans" as a Modernist document.

"Frank killed the grandfather of photography," one freelance

photographer commented to me. The fleeting gestures caught in the first

three photographs of "The Americans" are nowhere repeated; one soon gets

the feeling that Frank's sense of timing is based on catching a more

general and unlikely gesture. In effect, a stance rather than a gesture is

caught. Frank's method, however, derives directly from the decisive moment

syndrome. A look at some of the contact sheets presented in "The Lines of

my Hand" (Yugensha edition, pp. 87-90) frequently shows Frank pouncing on

his subject. |

| Ed Ruscha "Twenty-Six Gas Stations" (1962), "Various Small Fires

and Milk" (1964) "Thirty-Four Parking Lots" (1967), "Every Building on

Sunset Strip" (1966), A Few Palm Trees (1971), and more. It was Ed Ruscha,

a printmaker and painter, who gave photographers permission to do books

outside of the rigid photojournalistic traditions. |  |

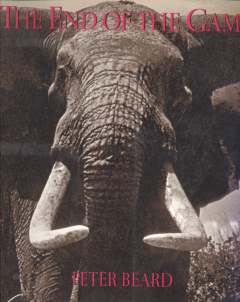

| Peter Beard "The End of The Game" (1967, 77, 88) The effect of

the book is entirely due to the editor who chose to do the presentation in

the style of what Northop Frye calls a 'Menippian Satire' or more commonly

known as 'encyclopaedic literature.' |

| The last exhibition catalogue of Hollis Frampton "Hollis

Frampton: Recollections, Recreations" (1984). Instantly recognizable as a

Menippian Satire, entirely befitting Frampton, who is actually a

filmmaker, but also one of the more astute photographic critics of his

day. See for example his collection of essays "Circles of Confusion" (see

below). |  |

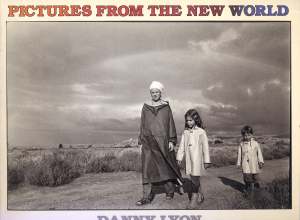

| Danny Lyon "The Bikeriders" (1968), "Conversations with The Dead"

(1971) Chicago based bikers. There is more by Lyons. I especially like his

"Pictures from the New World" (1981) |

| Lee Friedlander "Self Portrait" (1970),

"The American Monument" (1976) His compositional strategies show up in

"The American Monument" and are at times impenetrable. |  |

| Gary Winogrand "Stock Photographs" (1980),"The Animals" (1969),

"Gary Winogrand" (1976). |  |

| Duane Michals "Sequences" (1970) and

others. There are a number of other. Some are very cute, few have any

depth. But they were very popular. |

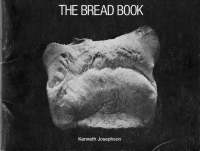

| Ken Josephson "The Breadbook" (1974) A great response to the

popular Duane Michals Sequences, and typical of Josephson's laconic

approach to photography, and with a typical show of effortlessness. Not an

astounding success, for the book only sold for $3.50, but one of the best

visual critiques ever. It ought really be listed under "Criticism" below.

See [Visual Criticism in Photography] for an

article on the Bread Book.

|

|

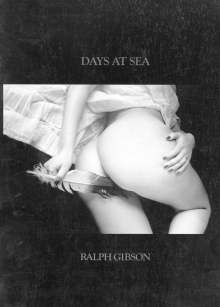

| Ralph Gibson "The Sumnambulist" (1970), "Deja-Vu" (1973), "Days

at Sea" (1974) Great sequencing, learned from Robert Frank. But no clear

message to me. Gibson was Lang's archiver before running into the work of

Robert Frank, which transformed him. He left for NYC, and even edited some

of Frank's films. He is an astoundingly astute photo-book editor.

|

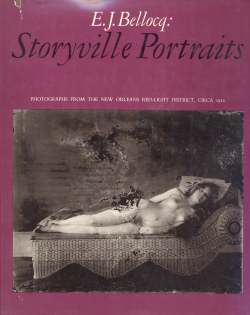

| E.J Bellocq "Storyville Portraits" (1970, edited by Friedlander)

A great book of calling cards for New Orleans whores. |  |

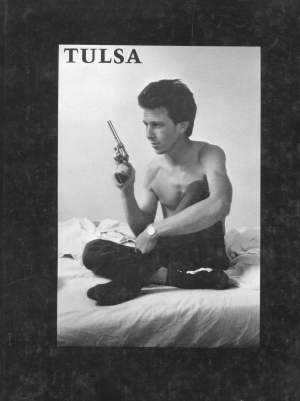

| Larry Clark "Tulsa" (1971) This became the most famous teaching

example among photo educators in terms of getting ideas across with

minimal text. But also a stunning book, since Clark was a participant in

the drug and gun scene, not an observer. Edited by Ralph Gibson -- which

is the strength of the book.

Clark's "Teenage Lust" (2 eds) pales by comparison. Introduced as

an autobiography, the book carries a rambling unpunctuated text, and is

filled with naked teenagers. The intriguing title was promised for nearly

10 years, finally came out in 1983, and republished later with more naked

teenagers. |

| Doon Arbus (ed) "Diane Arbus" (1972). Diane Arbus set the new

limits for photography in the 1970s, passing beyond all the boundaries of

what was allowed. Attendance at the exhibition of her work at MoMA

exceeded all other exhibitions of photographs. |  |

| Danny Seymour "A Loud Song" (1971) Edited by Ralph Gibson also. A

thin, minimal book, and mostly a story of getting off drugs - but

autobiographies don't sell well. Seymour is related to the Chicago Seymour

photographers, did camera work for Robert Frank. Drowned at sea on the

West Coast after the Rolling Stones got him back on heroin.

|

Robert Frank "The Lines of my

Hand" (1972). There are three editions, The first is an extensive, cased,

and large book, done in Japan, partially in Japanese. The second version

was edited down to a paperback by Ralph Gibson -- this is the one that

really packs some emotional power. And finally, there is an expanded

expensive glossy reissue by the Houston Museum of Fine Art, which loses

that power.

| Bill Owens "Suburbia" (1973) Wonderful. Only a close reading

determines that all the "recorded dialog" is made up by the photographer,

not that it is not uncharacteristic. |  |

| Clarence John Laughlin "Clarence John Laughlin" (1973) An

absolutely gorgious book, centered on old New Orleans and environs, by a

romantic photographer who probably insists on adding way too much

interpretive text. |

| Michael Lesy "Wisconsin Death Trip" (1973) Entirely composed from

19th century found photographs. |  |

| Ralph Eugene Meatyard "The Family Album of Lucybell Crater"

(1974) Meatyard's photography is outstandingly bizarre and surealistic.

This book is the only whole-book effort, although it will disappoint you

if you are into 'nice photographs.' |

| Gaylord Herron "Vagabond" (1975) One of the few more-or-less

general "my greatest hits" I would allow for admission to this pantheon.

It is autobiographical, structured, and closely edited. |  |

| Michael Snow "Cover to Cover" (1975) he is a Canadian film-maker.

A shot by shot compilation of front and back photographs which run through

the book like a film. At some points you will not know in which direction

you are reading. Totally iconoclastic and surreal. |

| Emmet Gowin "Photographs" (1976) Gowin received considerable

press in the late seventies for his presentation of photographs as

snapshots of rural family life (his family), with naive romaticized

overtones. View camera work, and frequently striking. His subjects make

the book. |

| Nancy Rexroth "Iowa" (1977) The standard of Diana Camera work,

competing with Conner, below. |  |

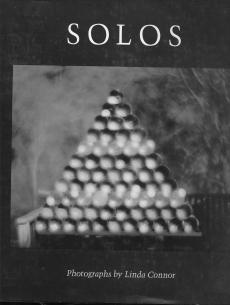

| Linda Conner "Solos" (1979) This book set the standard for

soft-focus camera work. |

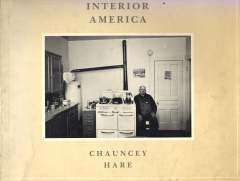

| Chauncy Hare "Interior America" (1978) People of the Alleghanies,

and a very touching if not outright heart wrenching. |  |

| Marcia Resnick "Re-visions" (1978) A Lolita-like envisioning of

staged photographs of the thinking of a young girl in the third person,

dismissed by the photo community, but absolutely wonderful (dedicated to

Humbert Humbert). |

| Keith Smith "When I Was Two" (1980, 2nd Pr) Offset, but photo

image based. A sort of coming-out book. Keith is a book maker.

|

|

| Linn Underhill "Thirty Five Years / One Week" (1981). Offset, but

entirely photo-based. A stunning book in effectively presenting grief.

|

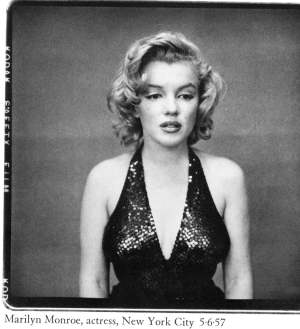

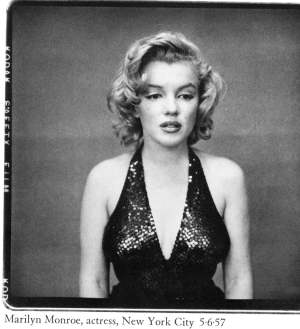

| Richard Avedon "In The American West" (1985) Full body straight

shots, stunning, no text. Shown here, though, is a shot from his

"Portraits" (1976). That work should be a primer. He had a reputation of

wearing his sitters down. Look at Marilyn Monroe. Eisenhower looks as if

his eyes are starting to wander. But he left that behind with "In The

American West" where most images were made before the sitter was

ready. |  |

Histories and Criticism

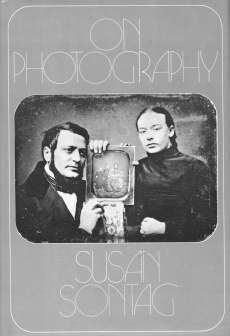

| Susan Sontag "On Photography" (1977). Disturbing to the

photography community in the 70s, because it is written by an outsider,

and caused endless discussions. Very varied in all the considerations she

brings up, but not deep. Still, a must-have book, which you will underline

and annotate page by page. |

| Hollis Frampton "Circles of Confusion" (1983). Absolutely my

favorite book of photographic criticism, but partially because of the

essayist's style (he covers some alternative film also). A book I have

read any number of times. Blows Sontag away. |  |

| Nathan Lyons "Notations in Passing"

(1974) A text-less visual critique on photography which goes over most

people's heads. Lyons runs the Visual Studies Workshop (Rochester NY), and

is a past photographic curator. |

| Nathan Lyons (ed) "Photographers on Photography" (1966) Much more

interesting to read what photographers have to say about photography than

what other tell. From Adams through Weston (actually Abbott through White)

-- 23 photographers. |  |

| John Szarkowski "The Photographer's Eye" (1966) An attempt to fit

a broad aesthetic classification schema to photography, probably more

concerned with style than form. 172 photographs by others, at times

grouped with more concern for topic than aesthetics. Nice book though, and

of some considerable influence. |

| John Szarkowski "Looking at The

Photographs" (1966) One hundred photographs from MoMA's collection, each

on a page, and reflected on by Szarkowski. Well written, interesting,

perhaps somewhat annecdotal, but never dry or descriptive. The images are

in historical order. |  |

| Beaumont Newhall "The History of Photography" (1937, 4th edition

1964). Not withstanding various trade histories, and various texts of Art

vs Nature snipings among photographers in the 19th and 20th century, this

is indeed the first major history of photography since its inception a

1839 which consideres it an art form, and for years remained as the

standard text . Robert Frank only gets brief mention. |

| Arnold Gassan "A Chronology of Photography" (1972). The

chronology is only an appendix. Most of the book is text, well written and

much more interesting than art history. There is a portfolio also of

images. |  |

| Robert Taft "Photography and the american Scene" (1937, dover

reprint 1964). Completely devoid of any pretentions toward art, this is a

history of photography as business and commerce in the 19th century. But

all the same, very interesting reading. Some 300 illustrations. |

| Patricia Bosworth "Diane Arbus" (1984). Unauthorized and

disputed, a gabby 'biography' which in the end does not provide all that

much insight. But meet Robert Frank's kids eating bananas, and all the

weirdness you could imagine about Diane Arbus. |  |

Photography books represent a very limited market,

often not selling more that 1500 before being remaindered. "The Family of

Man" catalog is the notable exception. But it is over for cheap

self-funded self-published photographic books after 1980. In the 70s you

could get a book out for $2000. That would take you ten times as much

today.

Since the 60s and 70s a wealth of "artists books" have appeared,

mostly visually based, but often unfortunately short. These span from

single books to issues into the thousands. See Joan Lyons (ed)

"Artists' Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook" (1985)

![[]](./bin/ailogo.gif)